Booktime: Interview with Hanna Nordenhök, author of Caesaria

Set in 19th century Sweden, Caesaria is a gothic novel following the life of a young woman who is confined to a doctor's mansion. As Caesaria grows up, she starts to question the world around her. We interviewed the author Hanna Nordenhök to discover her inspirations.

This exclusive feature is from the Sept-Oct 2024 issue of Booktime magazine, the essential guide to the most anticipated books of the season. Find a free copy of Booktime in your local independent bookshop.

"Caesaria holds within her a lot of my own inner landscapes and experiences of girlhood and womanhood, a landscape I believe many women can relate to"

What inspired you to write Caesaria?

I actually found Caesaria in a footnote. She suddenly appeared in a book I was reading on the history of obstetrics, and the fact that her story was mentioned in a footnote to an historiography of male hubris and scientific exploration felt very symptomatic. To me it said something about the invisibility of women in a male narrative where female bodies, paradoxically enough, played such a central role. Caesaria was a girl delivered in the 1860s through one of the first caesarean sections in Swedish history, and the novel is loosely based on it. Her deliverer was one of the pioneers of the emerging field of gynecology and obstetrics, a doctor working in Uppsala, who made his first section on a poor and unmarried woman, who died during the operation. The doctor named the girl Caesaria, after his own c-section, which was a fact that felt so symbolic: he named his own creation. This was a time of great zeal for surgery, a time of strong desires for dark, unexplored continents – and the female body was one of them. That little orphan girl intrigued me, and I started to invent my own Caesaria. She seemed to have something very particular to tell me and our contemporary world about our collective view of female bodies and about the history of women: a history of violence and confinement, but also of liberation.

Why did you decide to write it from Caesaria’s point of view?

I've always been interested in exploring the psychological mechanisms of power and subordination, and how the subordinated, as opposed to the powerful, perceive the world. So, paraphrasing Gayatri Spivak – can the subaltern speak? I really wanted to explore how a human being such as Caesaria, raised in confinement and isolation with the only source of information coming from her own prison guard, expresses her own existence, puts it into words. To find that voice was crucial to me and to the whole book. My Caesaria, that is a product of my imagination very far from the real case that I had as my starting point, is raised on a remote farm by her deliverer Doctor Eldh, where he keeps her as something like a trophy, but also as a confidante, a witness to his own scientific achievements. How does a trophy, a prisoner, speak? With which, or with whose, words? I think Caesaria holds within her a lot of my own inner landscapes and experiences of girlhood and womanhood, a landscape I believe many women can relate to.

The novel is set in the 19th century, but also has a timeless feel to it. Do you see it as an allegory, or a fairy tale?

To some extent I think all literature has some allegory to it, just as there is a level of fairy tale to all human life... But literature can't be too deliberate, you have to work with the unconscious and lose control of your own images as a writer, be swept along by the exploration rather than knowing everything about it: that is, I never thought about Caesaria as an allegory when I wrote the novel. But it's also true that I, to some extent, consider all of my books being explorations of different zeitgeists: spirits of eras and times, with all such spirit’s inherent collective notions, psychologies, ideological and visual imageries – and there maybe you have the allegorical too. Caesaria is a creature, a sort of Frankenstein’s monster, a creation of her epoque. But her story also has a connection to my life as a woman here, now, in our times. That bridge over time was important to me when writing her story. I think good historical novels need that ability to create this 'timelessness': they need to reflect something in our own contemporary lives, show a connectivity.

Did you do a lot of research into gynaecological practices of the time?

Yes, I did. And it was fascinating to dive into the medical journals of that era, when woman was such a peculiar object for study, a laboratory animal and at the same time this object for desire. Which makes woman extremely important historically, as a brick in the construction of a whole society, a whole political system where she was perceived as this shadow of man, his darker, more primitive counterpart. The language in these medical records was almost comical to me, a kind of strange poetry exploring this female bodily continent of echoing wombs, vagina farts, twisted pelvic bones and unexplored cavities that the doctors could put their hands on – and in...

Was the house where the book is set, Lilltuna, based on a real place?

No, it wasn't, it’s a pure invention. But it resembles houses where I have been, visited or lived: summer houses, farms, cottages in the woods. I don't think it is possible to escape your own experience as a writer, you write what you have lived, even in a distorted, fictional way: in that sense all literature is a kind of autofiction.

Do you think that Caesaria understands more about the world around her than she appears to?

I think there is a difficult discrepancy between words and reality for her. Her only sources of information about the outer world are the Bible that her carekeeper Fanny reads to her and the doctor's medical records that he insists on sharing with her. And then she has the shifts of nature around her, a nature that lives and dies, gives birth and kills. She tells her story from this ambivalent position, trying to finally conquer her own existence, to understand the purpose of her lonely and peculiar life.

Which other authors inspire you in your work?

That is very difficult to pinpoint, there are so many books that have meant the world to me. My early readings of Agota Kristof and Swedish Birgitta Trotzig surely have shaped my writing. As well as some of Per Olov Enquist's novels, like Captain Nemo's Library, a fantastic, overwhelming book.

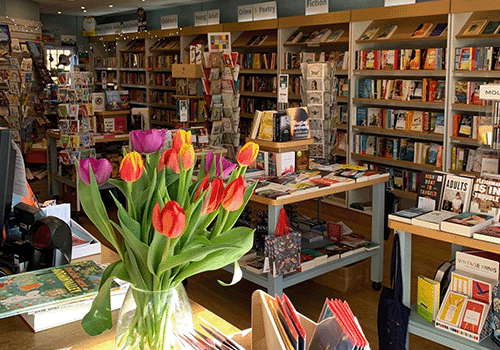

What do independent bookshops mean to you?

A lot – I love them. In Sweden there is a huge lack. Independent bookshops create spaces for the unexpected in a world where people’s reading habits are more and more instrumentalised and controlled by commercial needs. In that sense they are havens we need to protect, in order to make literature and reading survive.

In this extract, Caesaria describes her origins:

Doctor Henry Alexius Eldh cut me from his scrawny one's belly. Then he took me to Lilltuna. Perhaps he had simply dreamt of going about his work undisturbed, of a far-flung outpost where he could enjoy a spell of solitude or just be forgiven, somehow: for, after all, he was a man who fished for pearls.

He would come to tell me so much. As far back as I can remember, I would sit at the desk in Doctor Eldh's library, listening to his stories. I received them like a well receives the few shiny coins tossed into it, as if I were an opening that the words could slowly sail through, down to its murky bottom.

The library was sparsely furnished, with shelves along the walls that the doctor never fi lled. Sporadically, he'd lose his train of thought mid-sentence, which made me wonder if he remembered I was there. But then he'd look at me, dazed and thankful, as the evening light came through the tall windows, streaking the room and his large face red.

He would come to tell me so much.

Such as how, over in the city, he'd stood in the operating theatre's glaring light, by his scrawny one's bed, and observed that rigid body. How he'd seen to it that she was administered chamomile tea enemas, then chloroform, and powder to calm her on waking. Nonetheless she'd lain, still and dead, turning blue before him in the next day's sun, and the rain had stopped.

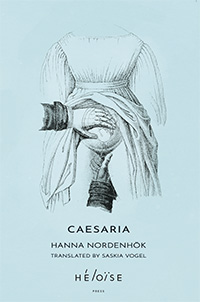

About Caesaria by Hanna Nordenhök

In 19th-century Sweden, a baby girl is born from a C-section performed by a renowned obstetrician. This is a rare surgery to survive for a baby, and the doctor keeps her in his mansion as a trophy. He names her Caesaria. Under constant supervision, she will live a dollhouse existence, subject to systems of control and punishment, sharing with us everything she sees and hears.

Who are the doctor’s mysterious visitors? What is there in the outside world? Where does she come from? In a Gothic style, Caesaria explores the ways in which early gynaecology experimented with the female body which appeared as a cryptic landscape to be intruded, invaded, controlled. The novel won the Swedish Radio’s Prize in 2021.